(see also our companion article“Coal Taxes, Rents, and Royalties”)

Summary

Alaska’s mineral industry was worth almost $3 billion in 2009, but paid less than 2% to state and local governments, counting all forms of taxes, fees, and royalties. Taxes on other industries are much higher: the oil and gas industry paid about 20% of its market value (which is still the lowest rate in the world), and the fishing industry paid around 5%. Coal mining also returns around 5% to the state. While low taxes for mining are attractive to corporations, some organizations and legislatures argue that they don’t represent a fair long-term value for Alaska’s resources, particularly since the vast majority of mining corporations are not Alaskan.

Variable state tax rates

The State of Alaska calculates the tax that it levies on different natural resource industries in dramatically different ways. A profitable large mine pays a flat $4000, plus 7% of its “net income” over $100,000. Oil and gas producers pay 25% of “net production value”. Leasing arrangements, profitability in a given year, and exemptions all modify the tax a company owes. In addition to statewide resource taxes, companies pay mineral rents/royalties to the state, corporate income tax, municipal and borough taxes, conservation surcharges, and other levies.

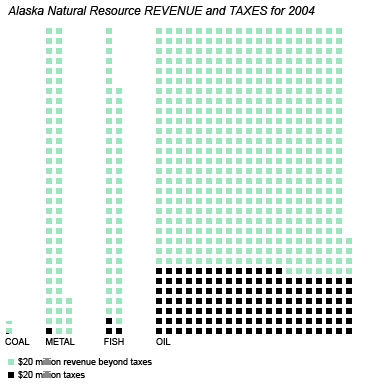

Two organizations investigated the 2003 tax receipts from the mining, oil, and gas industries, calculating the combined rent, royalties, fees, and taxes as a percentage of the total estimated production value (wholesale market value) of each resource. Their reports highlight a particularly large difference in tax burden between mining and oil/gas production. Halcyon Research calculated that oil and gas producers paid about 19% of the total market value of the resource, compared to only 1.6% of market value paid by the mining industry. A staffer in the Alaska state legislature arrived at 20.9% and 1.6%, respectively, and calculated a comparable value of 5.2% for the fisheries industry. In addition to a much lower tax burden, mining corporations are allowed to deduct their state corporate income tax from their mining license tax, and new mines are exempt from the mineral license tax for the first 3.5 years of operation

Several legislative actions have unsuccessfully attempted, in recent years, to increase the amount of revenue from the mining industry. House Bill 58 (HB58), would have removed the 3.5-year exemption for new mines in the mineral license tax, only allowed cost depletion when calculating net income, disallowed the deduction of state corporate income tax, increased the current tax rates for mining by 2%, added an additional 11% tax bracket for mines producing over $1 million, and changed the calculation of state royalties from net income to net production value. This bill died in Spring 2012, but may be reintroduced in a future session. Ironically, at the same time the legislature passed House Bill 298 (HB298) which exempted gravel, rock, and sand producers from even the existing mining tax.

Arguments for and against low mining taxes

For

The current tax scheme in Alaska is very favorable to companies looking to develop mineral resources. A 2009/2010 report by the Fraser Institute ranked Alaska the 19th most favorable “tax regime” in the world, among all countries and US states. Within the US, only Wyoming, Colorado, and Nevada had more favorable tax regimes for mining. This is particularly important in Alaska where concerns such as lack of infrastructure and high operating costs could be discouraging for mining exploration.

The combination of favorable tax environment, vast undeveloped mineral wealth, and rising commodity prices has caused a boom in mining exploration in Alaska over the last decade. Both this exploration and presumed future mines provide high-paying new jobs and stimulate economic activity.

Against

Once mined, the mineral resources of Alaska will be gone forever and those resources can no longer provide jobs and tax revenues for Alaskans. The “best interest clause” of the Alaska state constitution states that “It is the policy of the State to encourage the settlement of its land and the development of its resources by making them available for maximum use consistent with the public interest” (Article 8, Section 1). And “The legislature shall provide for the utilization, development, and conservation of all natural resources belonging to the State, including land and waters, for the maximum benefit of its people.” (Article 8, Section 2) It may not meet this best interest standard to extract Alaska’s finite mineral resources under a low tax regime.

Despite relatively far higher taxes paid by the oil and gas industry, Alaska has received massive investment by oil and gas companies. Higher taxes could bring in substantially more revenue for the state. Such revenue from oil has allowed the state to create the Permanent Fund Dividend program and provide many services without any state income or sales taxes.

Hardrock mining can have major economic and environmental risks. Acid mine drainage, habitat destruction, and the risk of cyanide spills are all potentially expensive side effects if they are unmitigated. The state bears some of the risks, either directly, in the case of mining company’s bankruptcy, or indirectly through damage to other industries, ecosystems, and water quality. Not all of the “true costs” of mining (such as pollution) are priced into the process of mineral extraction. Increasing taxes can bring the cost of mineral development more in line with the true cost of mining and ultimately lead to savings for society as a whole.

Further Reading

Created: Jan. 19, 2018