See here for a newer PDF version of this journey writeup.

Start date: September 2012

End date: September 2013

Distance: around 400 miles

Mode of travel: packrafing and walking

- Journey Overview

- Journey Writeups

- Slideshow

- Susitna Hydro

** I completed this leg of the journey in September 2012.**

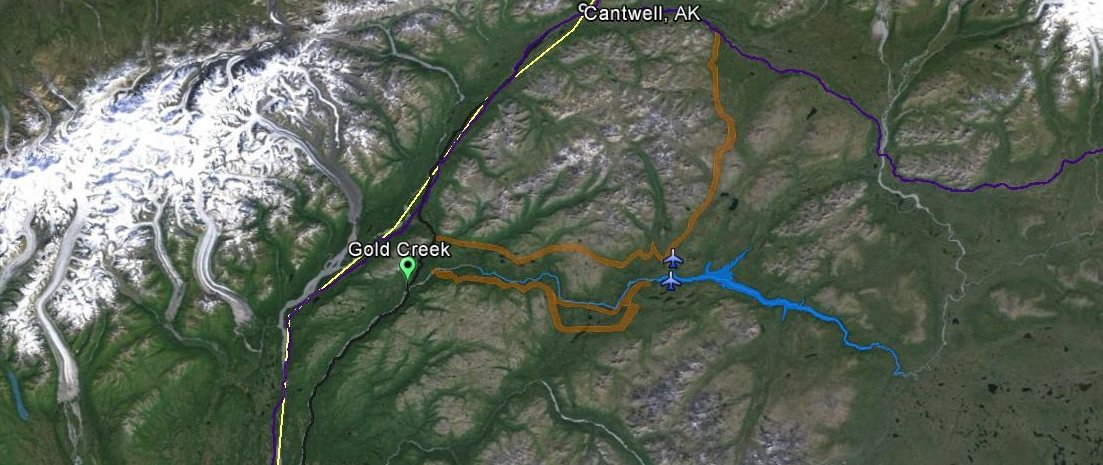

DAMSITE MAP

—

<a class="figure-caption__link" href="/photos/damsite-map/">Get Photo</a></figcaption></figure>It was a cool September morning at the peak of fall. The landscape was a vast carpet of red punctuated by patches of yellow, all speckled with irresistibly ripe blueberries. The weather was wet, windy, grey, and cold as I walked from the Denali Highway to the main Susitna Glacier, across open tundra through a land dotted with kettle lakes and bulging permafrost formations, ringed by rugged black mountains mottled with white caps. The nearby Clearwater Mountains earned their name - clear, clean water gushed everywhere. I hiked into a rainbow for a good portion of a day - a luminous arch cutting across a rainy, grey sky filled my field of vision while the sun warmed my back.

Curious caribou often observed me, wondering what type of strange tall creature had entered their realm. I came upon one in a ravine serenely licking salt, and surprised another pair who took to bounding through the thick creekside brush with an admirable grace and effortlessness. I soon struggled through the same vegetation. Later, I greatly appreciated a game trail which cut through nearly impenetrable dwarf willow and alder, but felt like cursing the caribou who had made it straight up through mud.

After several passes and a numbing crossing through a gray and freezing glacial lake I arrived at the main Susitna Glacier where I camped with an uninterrupted view across the glacier’s 1.5 miles of barren rock and ice to the mountains on the far side. It felt like a lonely and desolate, though fantastic, place as I fell asleep with the pitter of cold rain on my tent.

The next day, I climbed higher and further up the glacier approaching as closely as safely possible to the Susitna’s heights. Looking northeast to my right the glacier’s head clung to the high Alaska Range with Mount Hayes buried in cloud. The glacier begins as a multitude of small tributaries; each perched on the mountain sides - exposed ice filled with crevasses, steeply dropping down buried rock. Descending down the mountains, glacier joins glacier, converging into ever more massive tributaries, huge streaks of white cut by millions of micro-wrinkles, punctuated by long narrow strips of moraine - dark rock slowly eroded from the surrounding mountains. The glaciers bend and swirl magnificently where they join together.

Looking southwest to my left I could see the lower portions of the glacier, completely covered in moraine and in places filled with long lakes, resting entirely over and surrounded by glacier ice. Beyond the glacier I could see the main Susitna River flowing far into the distance, transitioning into a glacially carved, u-shaped, valley clad in vegetation. Joining its other main forks, the river eventually descended into evergreen forests. Altogether the main Susitna Glacier is about 20 miles long– a remote, alien, and beautiful place.

What changes will the future would bring to these glaciers? When passing the East Fork Glacier I noticed a distinct line resembling a bathtub ring far above the current level of ice and lake, a trim line likely indicating the extent of the glacier at the height of the Little Ice Age of the 19th century. Glaciers throughout Alaska are melting. According to Regine Hock, a glaciologist at University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Susitna glaciers and others along the Alaska Range are expected to decrease in mass by about 10% over the next 100 years, mainly in their lower reaches. After this initial melting, the glaciers are not expected to change too significantly. This is due to the altitude of the Alaska Range buffering much of the effects of increased global temperatures. Contrarily, glaciers on the coast, like the Malaspina Glacier, will take the brunt of the effects of warming.

The next morning brought low gray clouds and wet snow; winter had made an early appearance. I spent the majority of the day making my way to the toe of the glacier on a route through the glacier itself, paddling across its lakes and dragging my packraft over a brutal, confusing labyrinth of moraine - a thin layer of rock on steep slippery ice riddled with small pools. It was a long, tiring struggle, but beautiful with sheer, strangely patterned blue walls of ice, small icebergs, and dripping ice caverns. While I was paddling in the glacier a pair of small brown birds of prey flew above me, too fast for me to identify, clearly upset by my presence. They had found a refuge and a home in this seemingly inhospitable place.

During a series of lakes and portages, the terrain eventually shifted from rock and ice to cakelike, mucky mud and silty hills, making the portages difficult - a walk through shallow quicksand. As I paddled across one lake, I spotted a tributary up ahead connecting my lake and the next with a small rapid. I was quite happy to have a bit of current but as I approached I noticed that the water was pouring towards me, up the glacier! It seemed to defy gravity and I wondered how this was physically possible. It was initially quite dispiriting, but I soon spotted another hidden outlet. Upon entering it I could see a small reed bending slightly, leaving barely perceptible ripples flowing down glacier. Current at last! After such a difficult haul I was thrilled, certain that I had left the glacier behind and entered the main river. The reality of the situation soon became clear when the calm, slow river began to speed up, erupting into rapids forcing me to spend the next few hours slowly and cautiously scouting, portaging, and floating what I could through a series of steep, flushing river drops flowing off of the glacier’s toe.

At long last the river suddenly exploded in size. The float down the Susitna River had finally begun! It was swift and gray, with wide open views in every direction in what seemed to be an endless floodplain pocked by small brushy vegetation. I again moved towards a rainbow; this one massive, perhaps miles across, hugging the ground; an arcless horizontal line with wide bands of color. Before long I arrived at the Denali Highway, completing the first segment of my journey to the ocean.

Continue to Leg 2: Damsite and Devil’s

It was a cool September morning at the peak of fall. The landscape was a vast carpet of red punctuated by patches of yellow, all speckled with irresistibly ripe blueberries. The weather was wet, windy, grey, and cold as I walked from the Denali Highway to the main Susitna Glacier, across open tundra through a land dotted with kettle lakes and bulging permafrost formations, ringed by rugged black mountains mottled with white caps. The nearby Clearwater Mountains earned their name - clear, clean water gushed everywhere. I hiked into a rainbow for a good portion of a day - a luminous arch cutting across a rainy, grey sky filled my field of vision while the sun warmed my back.

Curious caribou often observed me, wondering what type of strange tall creature had entered their realm. I came upon one in a ravine serenely licking salt, and surprised another pair who took to bounding through the thick creekside brush with an admirable grace and effortlessness. I soon struggled through the same vegetation. Later, I greatly appreciated a game trail which cut through nearly impenetrable dwarf willow and alder, but felt like cursing the caribou who had made it straight up through mud.

See Chris’s new website, and the other adventures he’s doing: Chris Dunn on Planet Earth

Created: Jan. 19, 2018