See here for a newer PDF version of this journey writeup.

Start date: September 2012

End date: September 2013

Distance: around 400 miles

Mode of travel: packrafting and walking

- Journey Overview

- Journey Writeups

- Slideshow

- Susitna Hydro

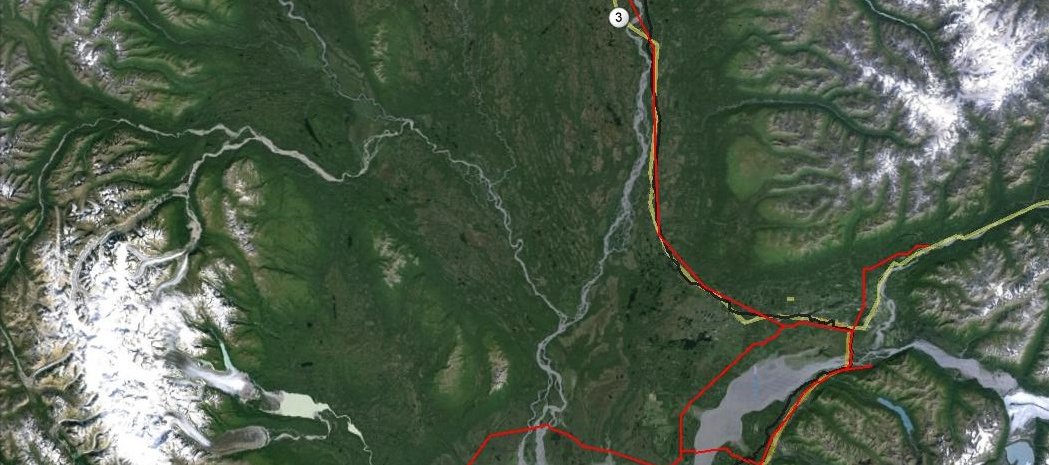

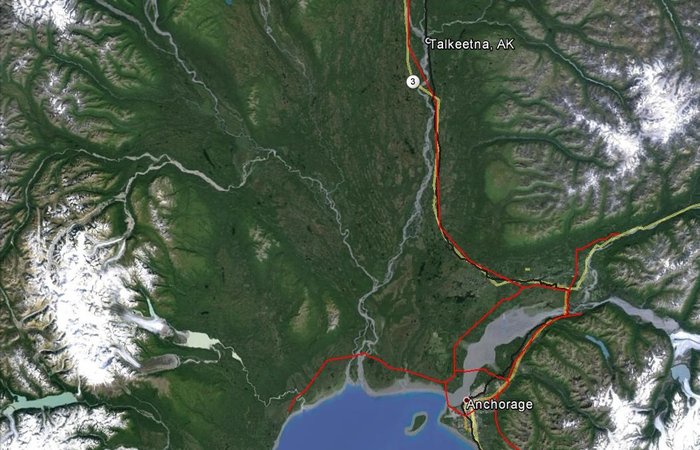

I completed this leg of the journey in September 2013.

After a few months’ hiatus I was back on the Big Su, launching from Talkeetna on my way to the Cook Inlet. As usual, I wasn’t quite certain what to expect, though I had been told that this this lower section of the Susitna braided out into dozens of smaller channels and so I was a bit concerned. Additionally, given the very minor drop in elevation, I expected to move quite slowly. Not only that but upon reaching the Cook Inlet I had to grapple with miles of quicksand-like mud flats and some of the world’s biggest and fastest tides.

Once again, I launched into the unknown on a cool fall morning with brilliant pink alpenglow shimmering off of the Alaska Range. The fall colors were out in blazing yellows mixed with lingering greens. The river was much clearer than it had been in mid-summer, now a murky green. The glaciated heights were beginning to freeze and so churning out less silt.

This turned out to be no lazy river; it moved quickly. There were even rapids and waves, often produced when the river would flow over or into dead trees.

The Parks Highway Bridge crossing would be one of the few signs of human industry on this leg of the Susitna. The highway bridge is also the third and last bridge crossing over the river.

It was amazing to see the Alaska Range and Talkeetna mountains fade away a little more around each river bend.

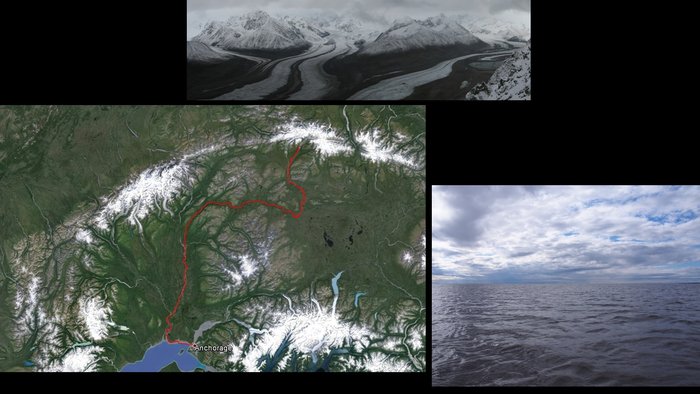

It was also neat to see the entire span of the Alaska Range including the more eastern portions from which the Susitna poured. The western portion of the range which includes Denali (Mt. McKinley) forms the headwaters of the Chulitna and Yanert Rivers, while the entire range forms a great curving wall of rock and ice that stops moisture and allows it to fall into the Susitna Basin through which I now paddled.

At I floated downriver different mountain ranges appeared in and out of view. At one point I could see five mountain ranges at once - the Alaska Range, the Talkeetna Mountains, Mt Spurr and the Todrillo Range, the Chugach Range, and Mount Susitna.

I cruised downriver at an impressive rate. At the Yanert Junction the Susitna balloons in size to mega-proportions. This, along with the great forests on either side, reminded me of the Amazon. During the night, I was kept up by the sound of rutting moose - grunting and crashing antlers; while ghostly howling disturbed the silence. It had the feeling of a wild and ancient forest. The river as a whole was prolific with life. Over the course of this leg I saw beaver, bears, and a moose that crossed the river but struggled for some time to climb up the opposite mud bank.

Before long I reached the last major piece of infrastructure: the transmission lines connecting the Beluga natural gas powerplant to Anchorage and the Railbelt grid. This powerplant is currently the largest in Alaska but would be ousted from the top spot if the Susitna dam were to become operational.

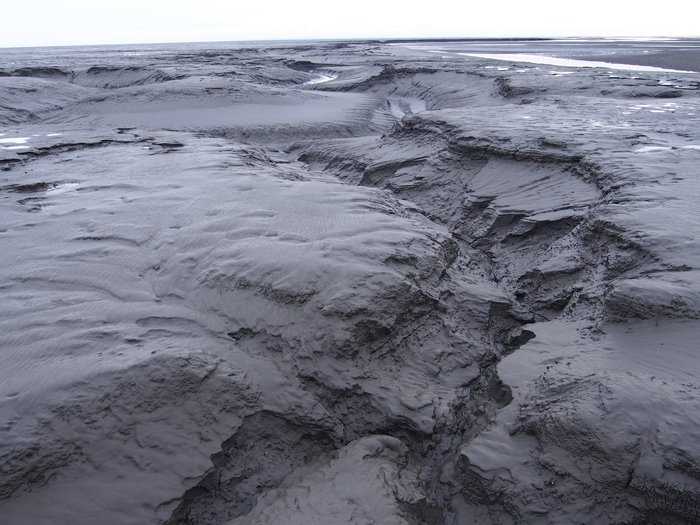

Surprisingly quickly, I arrived at the Susitna River Delta and the Cook Inlet, a world of ocean and mud. It was low tide and I was thus able to witness a vast region of flat muddy islands stretching out further than I could see. It was hard to grasp that the delta’s mud was silt washed downriver from the mountains and glaciers above. As I snaked through the branches of the river delta I noticed a distant boat beached far out in the delta, stuck until the next high tide. It turned out that on this leg I spoke to no one, and over the course of the entire river I had only spoken with a few AEA scientists on the second leg, and a couple of hunters on the first. I saw almost no one and when I did they were distant and encased inside of machines like this boat out in the mudflats.

I spent a night on the Susitna Flats amidst the ducks and waterfowl while the lights of Anchorage and the Fire Island wind powerplant twinkled in the distance. The next morning I had an exhausting walk across the grass and mud (mostly mud) to the Little Susitna River. Flocks of birds ascended and descended from the flats. The mud eventually creeped up onto everything. It was so dense, sticky, silver and strange. The mudflats were fascinating in their metallic silver-grey color and their incredible textures, often cut through by fantastic mini canyons. The Little Susitna itself was bounded within a tall, steep mud canyon. I used the river to carry me far out past the mudflats and after several unnerving miles I reached the Cook Inlet - the ocean at last!

Here at the ocean the Susitna ends, and, much like any other living thing, the river’s end might be thought of as a kind of death. It is simultaneously a rejoining and a loss of distinct identity. That which contained it, in this case the surrounding land, served as its temporal body; its banks gave it structure. This is hardly different than any other organism. An animal body is a container with thousands of miles of flowing red water encased within. At death the flow of an animal body ceases. It rejoins the land and the waters.

A few seals investigated my strange craft as I paddled up the coast towards Anchorage using the incoming tide to speed me along. I spent the night across the water from the city, having to clamber up a steep, sandy bank to find a camp spot. It was a unique experience - how many other big cities can be approached like this, can be viewed in such a way from a tent? It is amazing the difference a few miles of water makes. Where I camped seemed to be nearly a wilderness; there were only trees and birds while three miles across the Knik Arm stood buildings, concrete, cars, thousands of people. What would happen to this side of the Arm if a bridge was built, the cork holding back the sprawl pulled? Every so often the sound of an accelerating motorcycle would waft across to me, or a plane taking off or landing. A bald eagle flew right by my head as I sat watching the city - so close I had to laugh. I watched the tide go out and in. As it went out the surface of the water erupted into ripples and a great rushing sound, making me realize that the Arm is really a gigantic river that shifts direction every so often controlled by the moon and sun. It made me wander about the future of the Cook Inlet.

The next morning, I waited for the tide to go out before beginning my crossing - a prolonged endeavor that went well. A mysterious piece of debris bobbed along in the tide - a cylinder perhaps six feet across, highly corroded with rust, draped with thick marine rope.

Reaching the other side of the arm I plopped my way up through steep mucky mud to the city where I hopped over a fence onto a bike path and the solidity of concrete. Pedestrians eyed me while I packed up my filthy gear. I walked through town covered in mud, still wearing my drysuit and carrying my muddy pack, undoubtedly a spectacle as I waited for traffic at crosswalks. The journey was complete.

Ending at the ocean took me to the nexus of a significant portion of the Gulf of Alaska; a giant bowl with the Alaska Range forming its semicircular rim; one vast basin coming to a point; a good place to consider Alaska as a whole, its glaciers and rivers. Having visited the upper Susitna, including the proposed damsite, I can attest that this is a wild and special place, but one could reply, “Perhaps you are right in your defense of the wild, but this is just one place and its destruction is justifiable for the benefit it will provide in energy to humanity.” It must, however, be seen as a piece in a much larger context, Alaska as a whole, the United States as a whole, the globe as a whole. As mentioned above, there are relatively few places and rivers anywhere left in a wilderness condition, especially in the United States. When considered at this scale, the Susitna basin takes on a new meaning.

How much of our world are we willing to suck the life process out of so that it can provide us with trivial conveniences? Is there ever to be a line where we say here and no further? Is anything valuable in and of itself besides human life and comfort? What could we possibly create that is more valuable than the self-creative, ever-changing display of wild nature? Will we allow the given - nature’s spontaneity - anywhere except in relatively tiny, managed parcels of land? It is this which protected areas designated as wilderness, parks, and preserves have sought to protect, but these are managed areas and so have lost something in the process. The Susitna is remarkable in its essentially unmanaged wildness, which is simultaneously open to human-scale use, yet free from large-scale, exploitive industry - this, as much or more than anything else, is what makes it unique. Here is a place that is genuinely wild, one of a few left. Here is a large river that runs unimpeded to the sea, globally rare. Know this. And if we as human beings still choose to sacrifice that for our purposes, then let us at least acknowledge fully what we are choosing to do. Let us be honest. Places like the Susitna and its watershed are an integral part of what makes Alaska unique; rare, glorious, and irreplaceable. Here I have written about the Susitna River and the proposed dam, but I am also writing about our interactions with the world at large. Are we as human beings mature enough to ask ourselves these questions in all that we do?

A few seals investigated my strange craft as I paddled up the coast towards Anchorage using the incoming tide to speed me along. I spent the night across the water from the city, having to clamber up a steep, sandy bank to find a camp spot. It was a unique experience - how many other big cities can be approached like this, can be viewed in such a way from a tent? It is amazing the difference a few miles of water makes. Where I camped seemed to be nearly a wilderness; there were only trees and birds while three miles across the Knik Arm stood buildings, concrete, cars, thousands of people. What would happen to this side of the Arm if a bridge was built, the cork holding back the sprawl pulled? Every so often the sound of an accelerating motorcycle would waft across to me, or a plane taking off or landing. A bald eagle flew right by my head as I sat watching the city - so close I had to laugh. I watched the tide go out and in. As it went out the surface of the water erupted into ripples and a great rushing sound, making me realize that the Arm is really a gigantic river that shifts direction every so often controlled by the moon and sun.

See Chris’s new website, and the other adventures he’s doing: Chris Dunn on Planet Earth

Created: Jan. 19, 2018